The alpaca: foundation and symbol of Salt's success

The alpaca is a llama-like animal from South America that has been farmed for its wool for centuries. During the nineteenth century Titus Salt used alpaca wool to develop a hugely successful fabric. It made his fortune and allowed him to build Saltaire and Salts Mill.

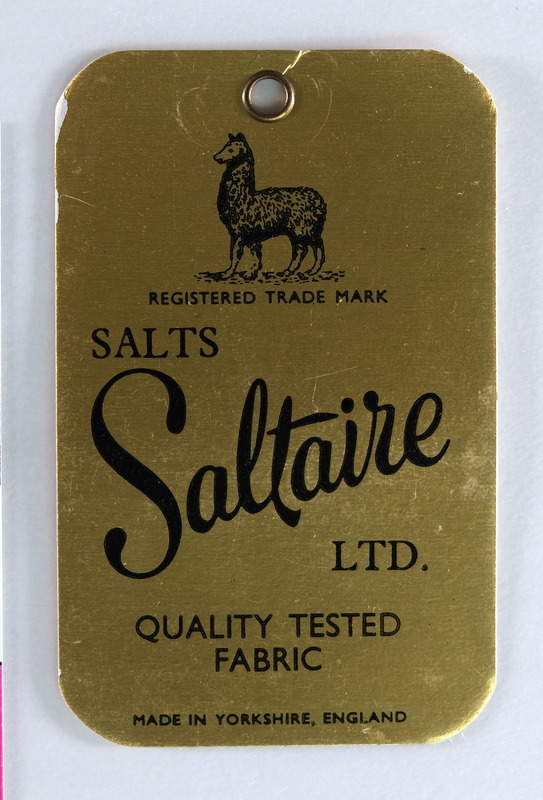

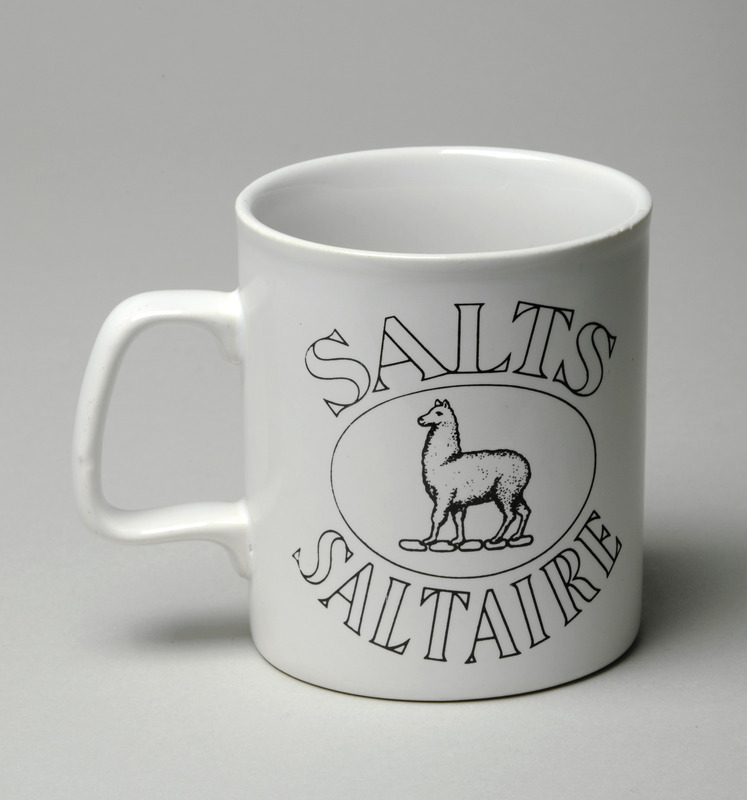

Alpacas became the symbol of Salt's textile business. They are found all over the buildings of Saltaire, on business documentation, on memorabilia, even on the crockery used for royal visits.

Our exhibition reveals the story of how the humble alapca has been so important to Saltaire.

What is an alpaca?

Saltaire has an enduring connection to the country of Peru because of one particular animal: the alpaca.

The alpaca is in the same animal family as the llama and is valued for its gentle manner and wool coat. It has been popular with the British public since it was first exhibited in London in 1811. Alpacas are, on average, 3ft tall at the shoulder, with long necks and large, pointed ears. Their wool has several desirable qualities, including its textile strength and softness to the touch. The wool comes in various shades of white, grey, brown and black.

The Quechua and other indigenous peoples of the Andes have used alpaca wool for centuries. The alpaca is a domesticated animal that has been an important part of Andean culture and traditions for thousands of years. The animals are of special cultural significance to the indigenous Quechua people in Peru, historically seen as a way of communicating with deities.

To this day, most of the world’s alpacas can be found in Peru. Their numbers are, however, increasing in the UK and across the world as more people choose to farm them and, in a few cases, also produce cloth from alpaca wool.

Bradford’s textile history

For hundreds of years, Bradford has been associated with the making and selling of cloth. The city became known as a textile trading hub, with regular markets drawing in merchants from around the region and beyond. The processes for making yarn and cloth were home based before the nineteenth century.

In the 1830’s, Bradford was changing rapidly. The population was increasing by tens of thousands, in line with several new mills that were being constructed. These changes happened because of the increase in the mechanised production of worsted cloth (where long yarn fibres are spun to make smoother, patterned cloth).

Consequently, there was an increasingly rapid growth in Bradford’s wool processing industry. The mechanisation of almost all processes progressed rapidly: by 1850, this was complete, and equipment became more advanced.

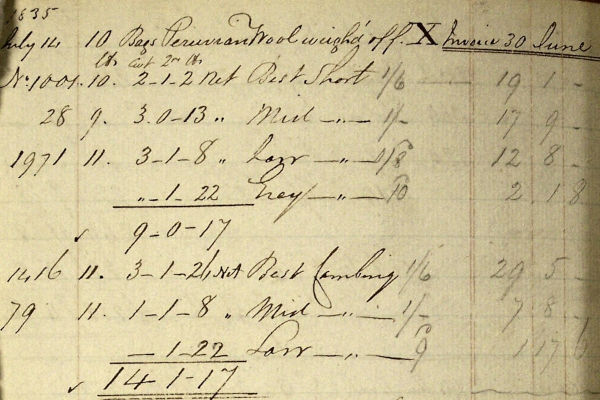

Titus Salt’s family were in the wool business. Titus’s father was a wool merchant and Titus joined the business which later expanded into spinning. He set up his own business in 1835 after his father had retired and the family firm, dissolved. Salt took advantage of the innovations in mechanisation, building a single mill, Salt’s Mill, completed in 1853, which took in raw wool and produced finished cloth.

Alpaca farming and wool sourcing

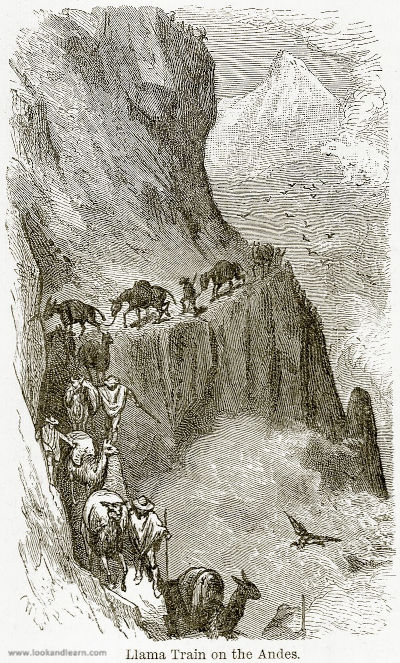

The indigenous people of the Andes domesticated alpacas and raised them on the high-altitude Altiplano, where the animals adapted well to the harsh conditions. This high plateau has freezing temperatures and intense sunlight, which alpacas endure with remarkable resilience.

Andean herders allowed them to roam freely, only gathering them occasionally for shearing, a process done once or twice a year between January and April to let their coats regrow before winter. Shearing requires careful handling, usually involving two people to hold the alpaca while a third trims the fleece.

Once sheared, the raw alpaca wool is spun into fine, strong threads, often softer than sheep’s wool. Traditional Andean methods are used to clean the wool with natural detergents like Sacha Paraqqy root and Illmanke plant, which create a foamy wash. This method involves a brief, vigorous hand wash that effectively removes dirt. After cleaning, the wool is hung to dry, preparing it for export to meet the demand for alpaca fibre internationally.

Saltaire’s links to Peru

Until Peruvian Independence in 1821, the Quechua were farming alpacas only for their own needs. The Peruvian export trade is less than 200 years old.

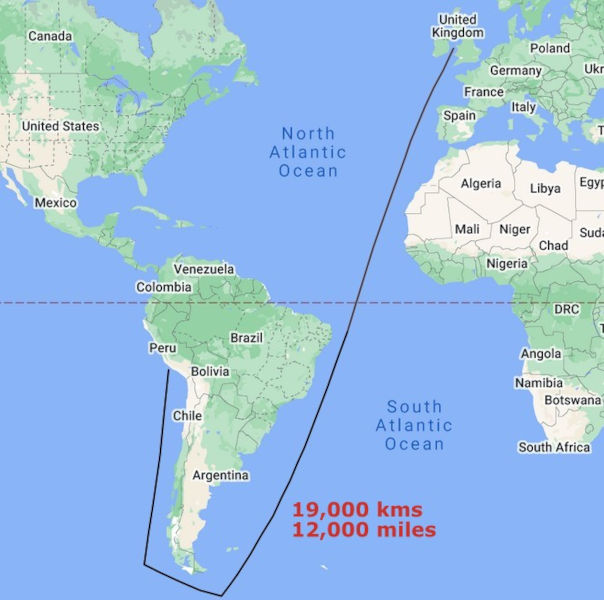

Transporting alpaca wool from the Altiplano to foreign markets involved multiple steps. Local sales fairs and direct transactions helped move wool to Arequipa, a hub for trade, where merchants purchased in bulk. Buyers, including English buyers, frequently attended the Vilque fair, establishing contracts with local producers for delivery in 8 to 12 months.

From Arequipa, wool was shipped from Islay to Liverpool, then made its way to Saltaire via the Leeds-Liverpool Canal (a vital route connecting Liverpool’s bustling docks with West Yorkshire), during Salt’s time. It was then processed into finished goods at the mills.

London docks also received shipments of Alpaca wool.

Titus Salt’s experiments with alpaca wool

The Reverend Balgarnie, writing in the earliest biography of Titus Salt, records that in 1834 Titus Salt first discovered some abandoned bales of alpaca wool in Liverpool, bought them at a bargain price, and went on to discover the wonderful properties of this material.

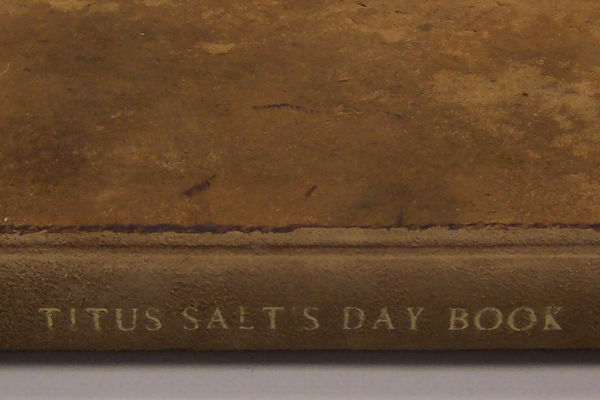

Salt kept a notebook between 1834 and 1837, detailing his experiments with alpaca wool. He began conducting tests on the wool with a group of trusted assistants, in secret. Salt also visited a dyer in Leeds who experimented with dyeing techniques. It took 18 months to perfect a fabric created by using alpaca weft (horizontal threads) with cotton warps (vertical threads).

They found the alpaca wool difficult to spin at first, having to adapt existing machinery so that the alpaca wool could be spun to produce an even and smooth fabric. The resulting alpaca-blend fabric was light, lustrous and with a similar sheen appearance to silk, but was more affordable to customers. These were all qualities which set his textiles apart.

Other Yorkshire manufacturers, such as Benjamin Outram in Halifax, had previously tried to work with alpaca wool but Salt was the only successful spinner of alpaca weft in Bradford at that particular time (eventually only two other firms in Bradford would develop the processes to use alpaca wool effectively). The alpaca fabric was popular worldwide and played a huge part in Salt’s success.

Other Bradford textile manufacturers also made their fortunes during the 19th century and the city was considered the frontrunner of the UK’s textile industry, creating a lasting legacy.

To read more about Titus Salt’s life see the biography on our website.

Extracts from Titus Salt’s daybook are available to view on the University of Bradford’s Special Collections webpages.

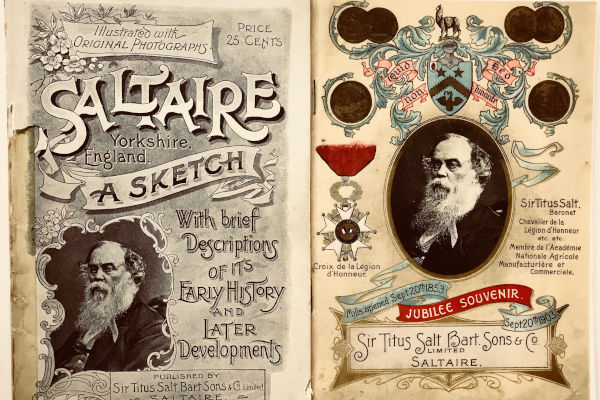

Branding

Over time, alpaca wool became closely associated with Salt's enterprise, and the alpaca itself emerged as an iconic symbol of Salts Mill and its high-quality textiles.

The alpaca logo first appeared during Titus Salt’s time, adorning business documents, trademarks, and product tags as a hallmark of the brand, including the motif on his own will. By the late nineteenth century, the branding extended to beautifully crafted items such as the plates purchased by Catherine Salt and Titus Salt Junior for Royal Visits in 1882 and 1887.

This evolution continued well beyond Salt’s death, with the alpaca emblem appearing on mid-twentieth century items like ashtrays and mugs. In 1953, to celebrate the centenary of Salt Mills, a metal badge with a drawing of an alpaca was made, showcasing the enduring use of the alpaca logo and its legacy.

The alpaca can also be seen on the buildings in Saltaire, for example on the face of the schools now known as the Salt Building.

The alpaca appeared almost everywhere – on furniture, in marketing, on household items and industrial items alike. The symbol evolved into a lasting icon, representing the mill (and by extension, the village) in its unique textile heritage. Through this branding, Salts Mill established a recognisable identity, and its impacts last until the present day.

Legacy

The legacy of Salt’s alpaca branding is still very much alive, with the alpaca motif remaining a central part of Saltaire’s cultural identity. Originally tied to Titus Salt’s innovative textile business, the alpaca symbol has grown into a reminder of Saltaire’s rich industrial past and its unique heritage. This motif appears throughout Saltaire, helping connect locals and visitors to Saltaire’s story and reinforcing the enduring significance of the alpaca.

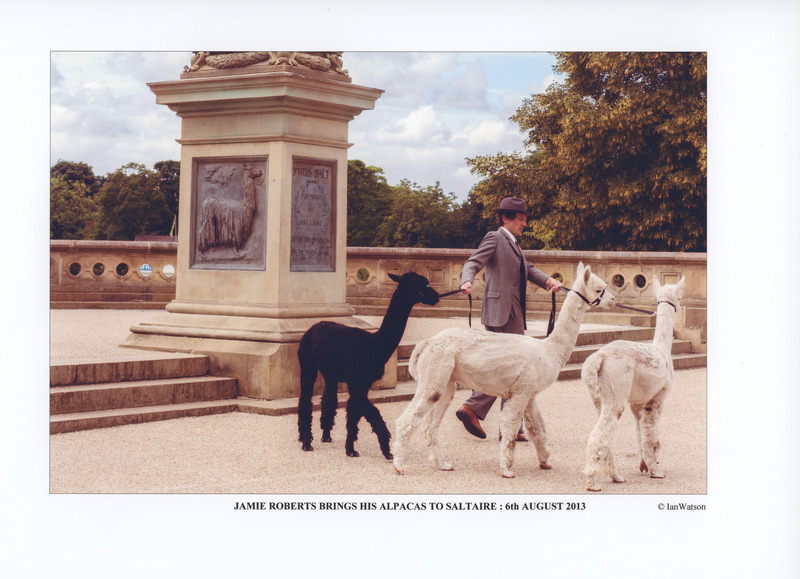

In Robert’s Park, for instance, alpaca statues honour Saltaire’s historical association with alpaca wool, serving as a landmark for people to appreciate, celebrate, and even question Saltaire’s links to the alpaca.

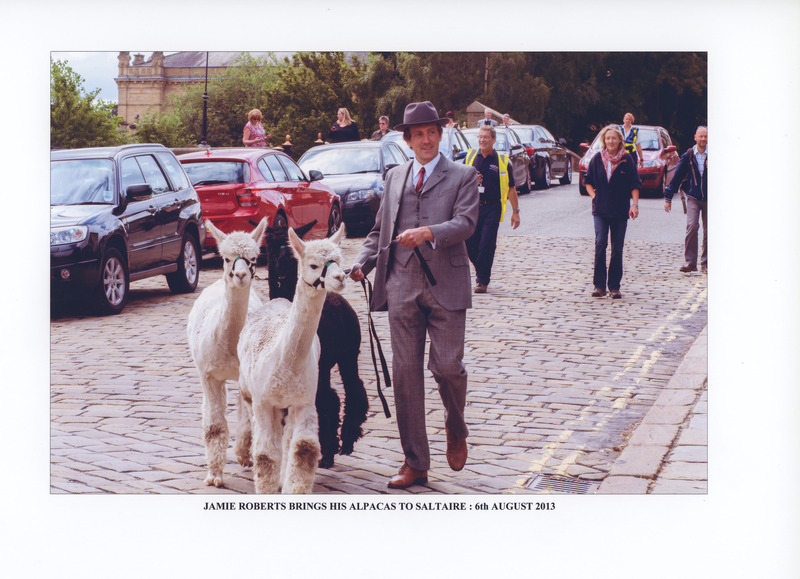

Live alpacas have also made appearances at community events and festivals, usually escorted by their keeper, Jamie Roberts, whose family also have strong ties to Saltaire, adding a lively and interactive connection to Saltaire’s origins. These events not only celebrate the heritage but also bring a piece of its history to life in an engaging way.

Although Salts Mill ended its manufacture of textiles in 1986, it’s likely that the alpaca emblem will continue to survive in the village for a long time.

You may also be interested in

Find items in our collection concerned with alpacas in some way

Read local historian Steve Day's fascinating research into the journey of alpaca wool from Peru to Saltaire

Find out more about how Titus Salt made his fortune from alpaca wool and used that success to found Saltaire