Saltaire's global connections

Although it is a small ‘village’ centred around what was a large textile mill, situated seven miles from the centre of Bradford, Saltaire has always been connected to places around the world. Its global significance is one reason it is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

This exhibition highlights some of those global connections, using items in the Collection which have a story to tell about links with other nations.

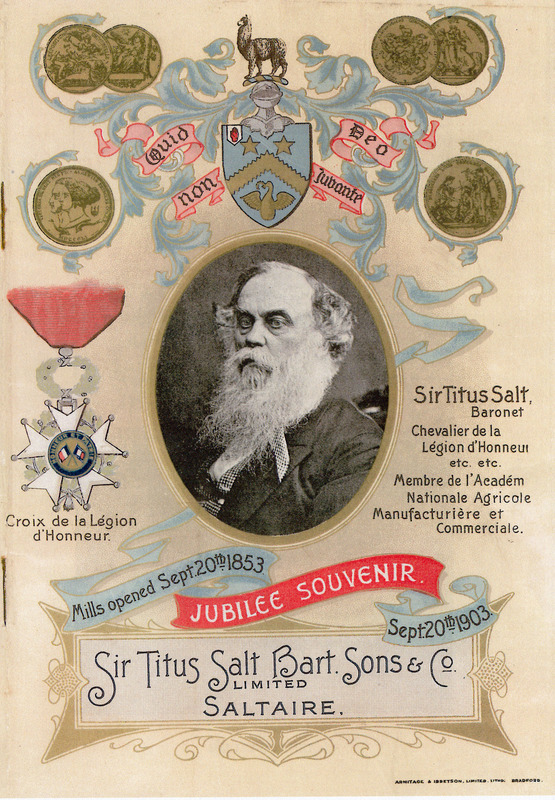

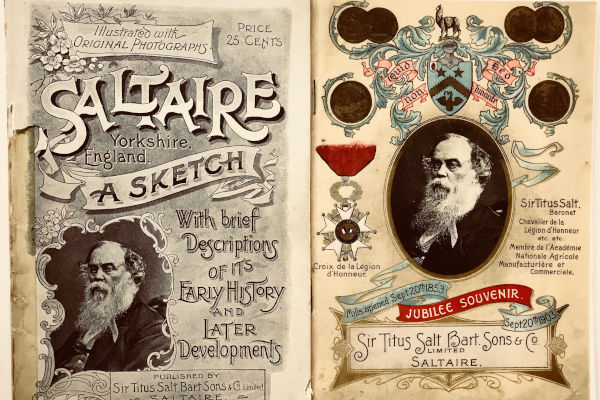

1867: France honours Sir Titus Salt

Sir Titus Salt was awarded the French Legion D’honour for his exemplary philanthropic approach to business in founding Saltaire, after he agreed to exhibit at the 1867 Paris Exhibition.

The major honour is referenced on the cover of the Jubilee edition of 'Saltaire, a Sketch History', produced in 1903 to commemorate the founding of Saltaire. The same book was also produced in America earlier in 1895.

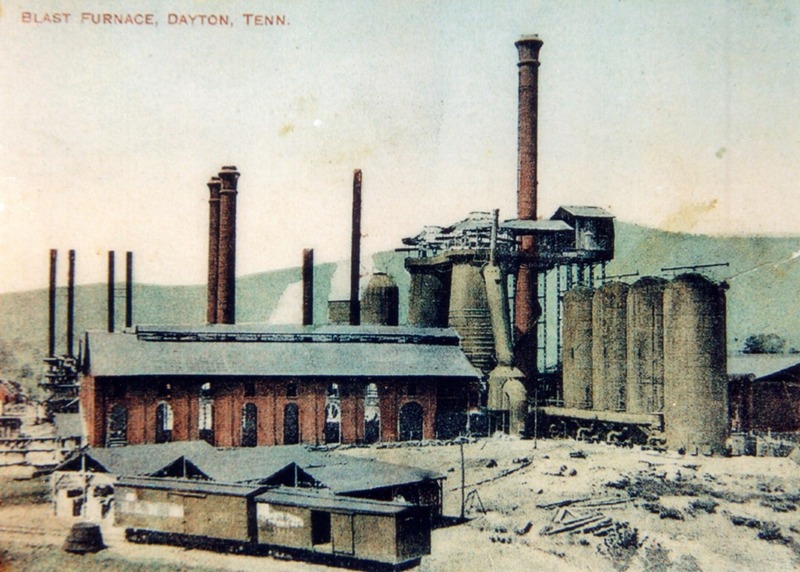

In the 1870s Alfred Allott and John Crossley purchased land at Smiths Cross Roads in Tennessee where rich coal and iron deposits had been found. When the business ran into trouble Allott obtained a mortgaged loan for £63,000 (about £7 million today) from the business of his close friend Sir Titus Salt.

By 1877 Allott was bankrupt. When Crossley died in 1879 the Salts' company directors acquired the land, now known as Dayton. In February 1883 they established the Dayton Coal and Iron Company to hold the land and mineral rights.

In May 1883 the New York Times reported that Titus Salt Junior and Charles Stead were visiting the United States with a Mr. Howson and two other gentlemen, who are among the leading manufacturers of iron and steel and are here to visit the Dayton coal mine, 25 miles from Chattanooga, to make extensive mineral explorations, examine its water power and resources generally...with a view to making large investments in the manufacture of iron, steel and cotton.

A year later Titus, Charles and a William Donaldson of Glasgow arrived in Dayton to announce an investment of $500,000 dollars. Two large blast furnaces with a capacity of 250 tons of iron ore per day, three fire brick kilns and 200 coke ovens were constructed as well as 200 homes, a managers house (costing $15,000), a company store, a schoolhouse and other social amenities. There is a sense of déjà vu between this and the building of Saltaire. What had been a small hamlet grew into a sizeable town over a very short period.

In 1892 the Salt business partners had to surrender their interests in Dayton due to the collapse of Sir Titus Salt (Bart) Sons and Co. Ltd. The investment the company had made in Dayton was a significant factor in the Salt familys loss of their business and the estate of Saltaire.

Read below about another, more personal connection between Saltaire and Dayton.

With thanks to Saltaire historians, Dave Shaw and David King for their research when visiting Dayton in 2012.

1887: The 'Japanese' statue from China

The Royal Yorkshire Jubilee Exhibition was held in Saltaire in 1887 to celebrate Queen Victoria's Golden Jubilee and more importantly, for Saltaire, to help meet the costs of the new School of Art and Science that had been built on Exhibition Road as a memorial to Sir Titus Salt. It was opened by Princess Beatrice and included exhibition stands, a concert hall, a bandstand, refreshment rooms and pleasure grounds and entertainments.

At the far end of the exhibition grounds there was a Japanese art and industrial exhibition in the form of a village reportedly 'peopled by Native Men, Women, and Children' and illustrating the 'industrial, social, and domestic life of Japan.' There was even a splendidly embellished Buddhist Temple.

The Shipley Times of 7 May 1887 reported:

A complete tour of the Exhibition is not made until the Japanese village at the East end of the Exhibition grounds has been visited and Mr. Tannaker Buchicrossan has provided there entertainment and instruction sufficient to satisfy the most exacting.

During building work on Exhibition Road in 1976 a sculpture was found that is believed to have been part of the village. It is now part of the Saltaire Collection.

The Victoria and Albert Museum have confirmed that the sculpture is actually Chinese.

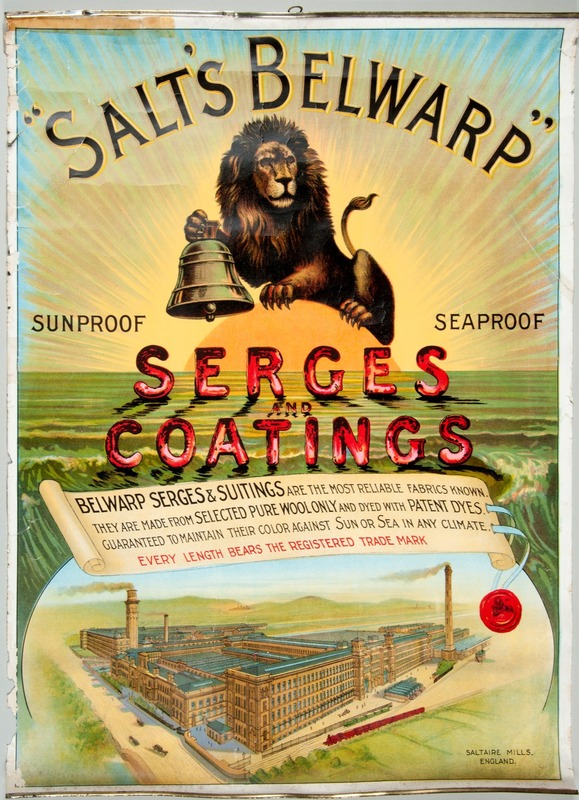

1890s: Belwarp and the Argentinian connection

'The Belwarp' was the trademark of a company in Argentina and was to become a well known trademark for Sir Titus Salt (Bart) Sons and Company Ltd.

The Argentinian company was purchased at some point by a consortium of business men, Isaac Smith, John Rhodes, John Maddocks and James Roberts who became owners of the Salt company in 1893. Maddocks was the sales director who travelled extensively and it is likely that he was involved in its purchase.

The Belwarp trademark developed a good reputation, indicating a high-quality cloth, ideal for the manufacture of suits, that was guaranteed not to fade. It is not clear when the originating company in Argentina was founded but the original trademark was registered in 1891.

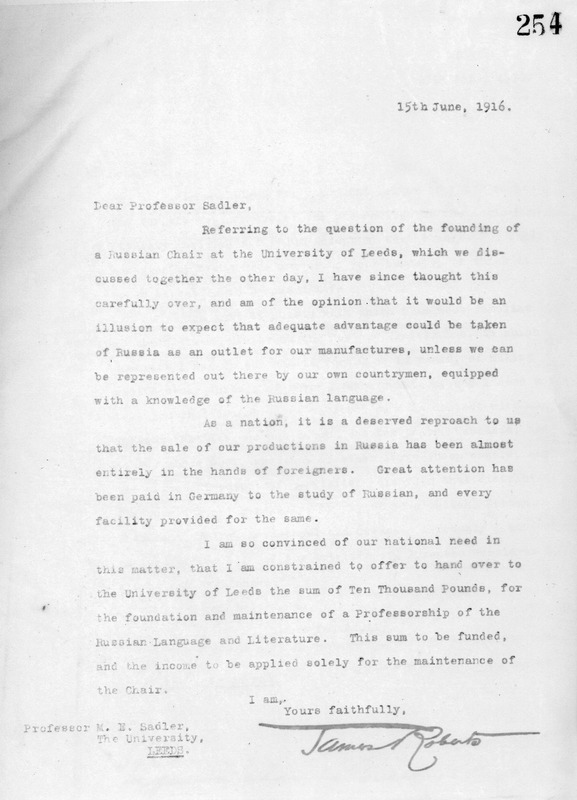

1910s: James Roberts' interests in Russia

James Roberts started work at 11 as a worsted spinner in a mill in Oxenhope, near Keighley. He rose from these humble beginnings to become a leading textiles businessman and eventually owner of Salts Mill and Saltaire, a success partly built on trading with Russia.

By the late 1880s Roberts was a successful Bradford mill owner and had spotted a business opportunity in the vast flocks of merino sheep being reared in Russia. He spent up to three months a year in Russia sourcing wool from large estates in Rostov on Don. He also started initial processing of the wool before it came to Britain so its source could be hidden from his competitors. His travels in Russia forged a strong attachment and Roberts became fluent in Russian.

In 1893 Roberts was part of a consortium of business men that purchased the failing Salt family business and Saltaire. Roberts gradually bought out the other partners to become sole owner by 1902. He revitalised the business and continued to support Saltaire and its amenities. But the First World War brought great challenges when it broke out in 1914.

At the start of the war he cancelled a trip to Russia 'to stand by' his workers. He had to deal with an immediate crisis because 90% of the exported yarn had gone to Germany and Russia and both countries cancelled their outstanding contracts. The mill was put on short time working but Roberts suspended the rents for the workers' homes in the village. Roberts reduced the cost of cloth to secure a government contract and eventually re-commenced exports to Russia, though at poor rates of exchange.

Despite his many problems, in June 1916 Sir James gave a gift of £10,000 (around £700,000 today) to Leeds University for the foundation of a professorship of Russian language and literature, believing that having Russian-speaking graduates was important for future business. Studies started in April 1917, just as the first Russian revolution was happening. When the Bolsheviks took control in October Roberts' investments in Russia were wiped out and he suffered a huge financial loss.

The loss of his Russian trade and the challenges of the war took its toll on Roberts and he sold the textiles business and the Saltaire Estate to a syndicate of Bradford 'Wool men' in 1918.

At the University of Leeds University, the chair of Russian studies thirved, interrupted only by the Second World War. It's heyday was the 1960s when there were 10 lecturers. Today Leeds has studies of the Russian Language in its School of Languages. Culture and Society and Russian History in its School of History, and the Library Special Collections holds the world-renowned Leeds Russian Archive.

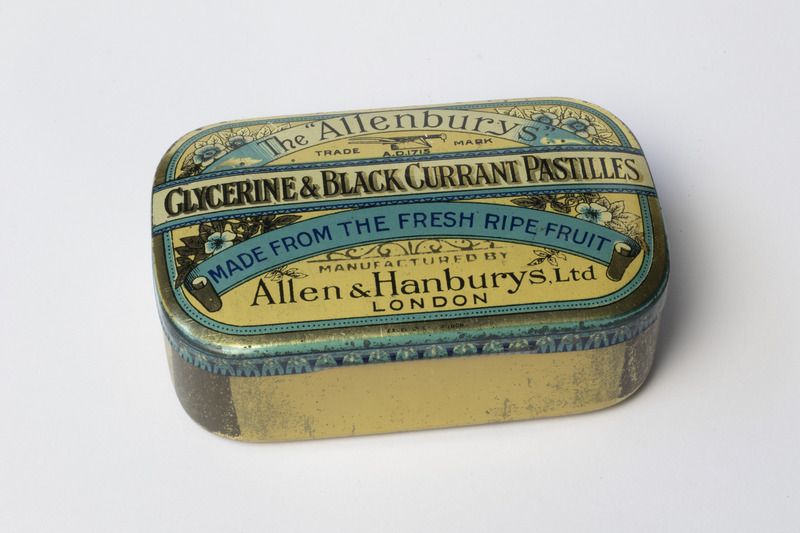

Acorns in a tin? Yes, we have some rather odd items in the Collection! These belonged to Isabel Salt, daughter of Titus Salt Junior and granddaughter of Sir Titus. She traveled frequently to Europe, both before and after World War One, and on one occasion brought back a collection of acorns. These arrived at the Collection, very well preserved, in an old throat pastille tin with a note stating:

Autumn 1918

These were picked up by M.I.Salt in the grounds of the Palace at Doorn Aumerungen (Holland) where the Ex Kaiser was then living.

'Doorn' had been altered to 'Aumerungen' (Isabel's spelling).

It's all rather mysterious though…and raises a number of questions:

Did Isabel really travel to mainland Europe in Autumn 1918, so soon after the end of hostilities? Would this have been possible?

Why was she uncertain about where she picked up the acorns, changing Doorn to Amerongen? Kaiser Wilhelm II did indeed go into exile in Holland, leaving Germany by train on 10 November 1918. He first lived in Amerongen, before moving to Doorn in 1920 – but surely Isabel would have known where she picked up the acorns, and not needed to correct it later? And would she have been allowed to walk in the grounds of the 'Palace' while he was still in residence?

We also have Isabel's passport showing she visited Holland in 1919, 1921 and 1926. Could she have picked up the acorns on one of these visits?

1940s: From Poland to Saltaire via the Middle East

Feliks Czenkusz was born on June 4 1920 in a village called Lakorz, in Poland, just 2 kilometres from the German Border. At the start of the Second World War Feliks embarked on a long journey that was to take him eventually to Saltaire eight years later.

He first escaped to neutral Lithuania but after a few months in a camp he was moved to Russia with other Poles. When Germany invaded Russia on in 1941 Feliks and the others were marched off again to board a ship and then a train travelling south. Arriving at a camp, Feliks found himself a member of the Free Polish Army. He recalled, 'we didn't know it but this was our first step to becoming free men'.

Feliks and his comrades travelled to Iraq and trained for a year before moving to the Allied front in the South of Italy. For two years, Feliks took part in battles across Italy, including the famed taking of the German stronghold of Monte Cassino by Polish troops.

When the war ended Feliks was not returned to, the now Russian-dominated, Poland. Instead in 1946 he boarded the 'Empire Pride' bound for Liverpool.

Settling first in Norfolk, Feliks moved to Bingley in 1947 to work in the textile industry. After 18 months, he got a job as a weaver in Salts Mill, Saltaire. He remained in work there until retiring in 1982, seeing huge changes in the textile business during this period.

1940s: Theresa Schistal moves from Austria to Saltaire

Theresa was born in a small village called Mattersberg, just outside Vienna, Austria in 1931, just as the Nazi Party were coming to ascendancy in Germany.

Surviving the trauma of the Second World War, Theresa found employment difficult to get in post-war Austria. She saught work in Britain through the European Voluntary Workers Scheme. In 1949 she travelled alone to Yorkshire and initially stayed at a European Voluntary Workers' Hostel in York. She gained employment at Salts Mill and came to live in the hostel provided for European workers based in the New Mill, just below the main mill on Victoria Road in Saltaire.

The young women were well looked after, although the two 'matrons' in charge of the hostel attempted to strictly control their lives, including imposing a 9pm curfew. Theresa would reminisce that many of the women would creep out of the windows once the all clear was given!

Initially Theresa was given employment in the spinning department at Salts Mill but she found the work to be technically difficult so was moved to the burling and mending department. Here Theresa learned new skills and became a 'passer' – looking at the work of others and using chalk to circle any patches in the cloth that needed to be re-worked. She learned to pass the work to the most skilled women to correct these pieces.

While Theresa lived in Saltaire she met Ronald Mortimer at a local dance and later married him. Theresa had a son but continued to work in Bradford's textile mills until until finally taking a job in Bradford's town hall.

1957s: Three Italian sisters travel to Shipley

Dora, Velia and Margherita Ricciardo were born before the Second World War in Avezzano, a village near Sessa Aurunca and 40 miles from Naples. They helped in their father's agricutural business, including harvesting grasses, or stramma, some of which was pulled into twine and plaited for rope making. The skills they developed would prove to be useful in the British textile industry.

After the Second World War, Italy's economy was shattered and the family struggled until their father's business went bankrupt in 1956. Dora's brother had heard that British textile companies were seeking 'girls' to work in their mills, with travel costs paid by the recruiting firms. Dora and Velia went to Naples to be rigorously interviewed and undergo a thorough medical examination by the British recruiters and a team of seven doctors. They were successful and with short notice left Italy to arrive at a hostel in Shipley on a March evening in 1957. Their younger sister Margherita later came to join them.

The sisters started work at Henry Mason's Mill, but their experiences were simiar to the many Italian women recruited at the same time to work at nearby Salts Mill. Dora was employed as a 'gill minder', which involved looking after two large boxes of yarn to make sure that the weight was always balanced. 'When pieces of yarn were broken, I had to mend/tie these and then load them on to the bobbins. Where yarn was broken, I had to put a cross onto the bobbins'. Margherita worked in the winding process room and earned £4 a week like her sisters. They sent £10 each a month home to their parents, a welcome relief for the family in Italy.

The weather was a challenge, with the sisters, and their clothes, unused to the cold and the snow. The sisters also experienced some prejudice from - a few - of the British people they met and worked with. Some people said 'you don't belong here' or 'if you don't like it go back to your own country'.

Living in the hostel with around 40 other young Italian women was great fun except for the small, shared kitchen. The sisters attended Belle Vue Upper School on Wednesday and Thursday evenings for voluntary English lessons. At work they got by with sign language at first and did make many English friends, but the language barrier was very hard at times. 'It was always nice to get back to the hostel where we could all understand one another'.

Dora, Velia and Margherita continued to work in England, and all eventually married - St. Aidan's Church in Baildon, by Father Villani from the Italian Mission in Bradford - and had children. They are clear that they have had a happy life and would not change how life has been for them in Britain.

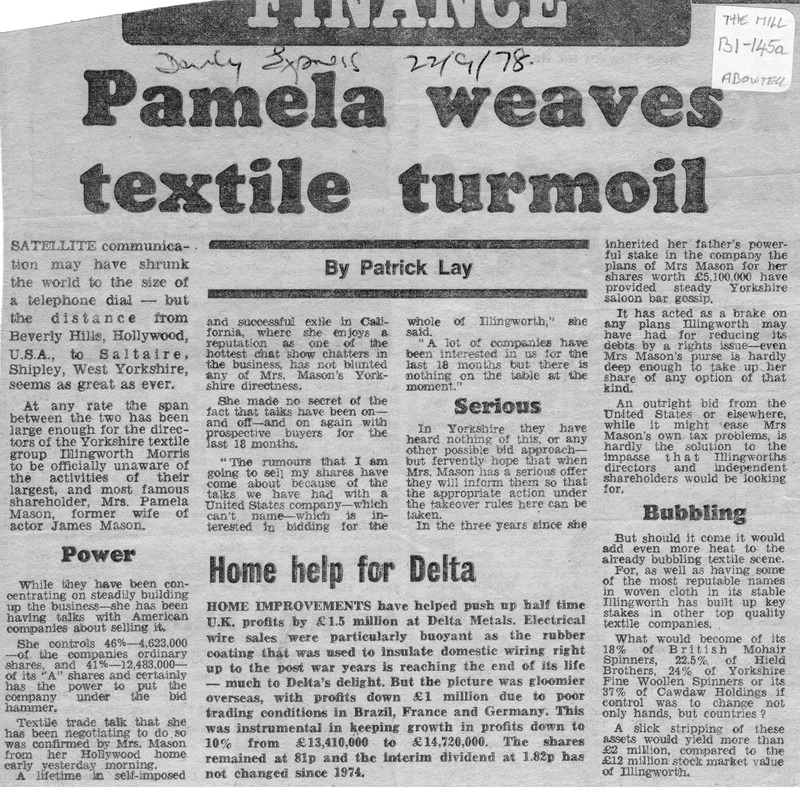

1970s: Beverly Hills comes to Saltaire

Isidore and Maurice Ostrer were born in the late nineteenth century in Whitechapel, London to Ukranian refugee parents. The brothers established a merchant bank after World War One. In 1920 they helped to float shares in the companies Daniel Illingworth (Bradford) and William Morris (Sowerby Bridge) to form the company Illingworth, Morris, retaining some shares for themselves. For a considerable period, they also owned the film company Gaumont British but sold their interests to J Arthur Rank in 1941 to concentrate on developing Illingworth, Morris.

In 1958, they made a surprise takeover of Salts (Saltaire) Ltd. the owners of Salts Mill, establishing Illingworth, Morris as probably the largest textile group in the world.

Both Ostrer brothers died in 1975 leaving Isidore's eldest daughter Pamela as the sole executrix of their wills in control of 46% of the company's shares. Living in Beverly Hills, Pamela brought a hint of Hollywood to Saltaire. She had acted in British films, had married the leading actor James Mason, and later became a television personality and chat show hostess.

Pamela urged the directors to promote their products more in the USA and appointed her son Morgan to the board. However, as the firm began to struggle financially she became angry with the 'Yorkshire Directors' and appointed two further American directors, including Caspar Weinberger, who was shortly to become Ronald Reagan's Secretary of Defense.

The 'Yorkshire directors', including Donald Hanson, the chair of Illingworth, Morris, were bombarded by faxes, telephone calls and media interest as a 'war of words' progressed. In 1981 the Directors led by Hanson called an Extraordinary General Meeting with a proposal to dismiss Pamela and Morgan from the board. Surprisingly, the board defeated Pamela Mason who then sold the shares she controlled to Alan Lewis's Abele company for less than their value.

Donald Hanson remained in post for another 3 years, managing to reduce Illingworth, Morris's debt significantly. He retired in 1983 just before most textile processes were transferred from Salts Mill and it was put up for sale.

2012: A teapot returns from the USA

As recounted above, there is a strong historical business connection between Saltaire and Dayton, Tennessee. There is also a more personal story to be told concerning a well-travelled teapot…

In the 1860s, William Hanson moved to Saltaire to work as a fitter at Salts Mill. Sir Titus Salt valued William's engineering skills highly and eventually promoted him to head of the Engineering department for the Mill.

William Hanson's youngest daughter Eva became a school teacher in Saltaire. She was engaged to Percy Johnson, a senior book-keeper at Salts Mill. Around 1884 Percy travelled to Dayton, Tennessee with Titus Salt Junior and Charles Stead to oversee the finances of the Dayton Coal and Iron company that they had founded in 1883. Eva travelled to Dayton to marry Percy Johnson in 1885 and among the wedding gifts that went with her was a teapot. Percy and Eva remained in the United States and eventually settled in Canada.

Back in Britain, Eva's grand-nephew Donald Hanson rose through the ranks of the textiles giant Illingworth, Morris that purchased the Salt business in 1958. Donald eventually became chair and joint chief executive for Illingworth, Morris in 1981. In May 2012 Saltaire Historians Dave Shaw and David King were invited to visit Dayton, and Donald requested that they enquire about his great aunt and uncle to find out more about their time in Dayton. Donald had many fond memories of Aunt Eva's visits back to Yorkshire with gifts of American toys that could not be found here.

In Dayton, Shaw and King contacted Pat Guffey, County Historian for Rhea County, and he had an immediate answer 'Percival knew my great grandparents and presented them with a teapot brought from England, when he finally left Dayton' – asking 'would you like to have it, to give to Mr. Hanson'.

The teapot was brought back to Saltaire where it was presented to Donald, who then donated it to the Saltaire Collection.

The Saltaire Collection is very grateful to Dave Shaw and David King, for this wonderful item and its story.

You may also be interested in

Browse the stories of some of the people who lived in Saltaire, worked in Salts Mill, and travelled from afar to start a new life in the village

Browse the Isabel Salt Collection which contains photographs, clothing, letters, travel diaries and newscuttings as well as a tin of acorns